T.E. Lawrence: A Love Affair with Speed

I have long mused that perhaps the most challenging task for a motorsport journalist is how to adequately describe to a non-rider what it feels like to ride a motorcycle. To those of you reading this, you are probably already indoctrinated to the soul-seducing capabilities of motorcycles. So, in essence, I’m preaching to the choir.

But how do you convey to someone who has never ridden a motorcycle the sensation of riding?

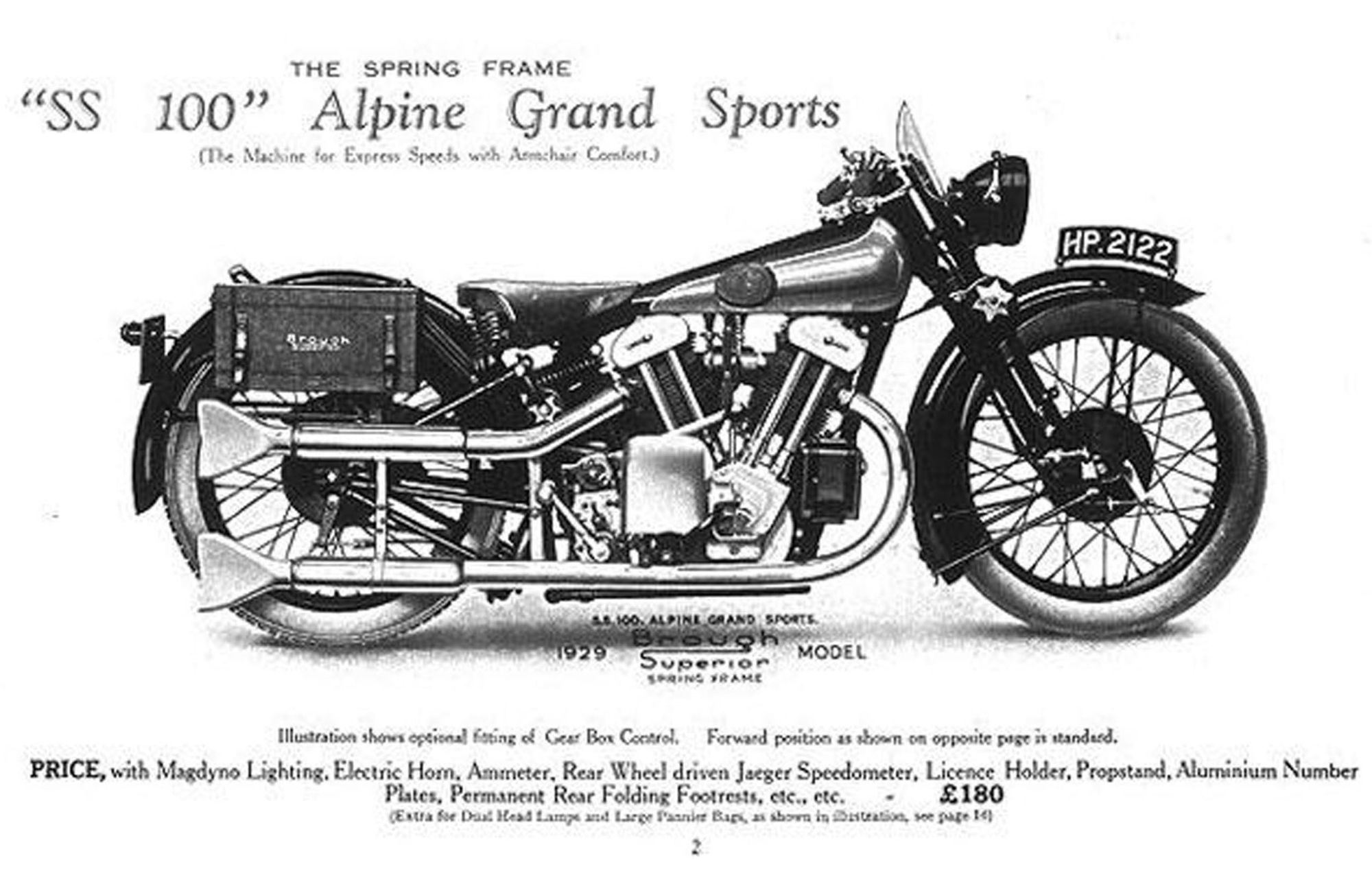

There is one author who consistently tapped into a kind of spiritual ether whenever he deigned to write about motorcycles. That is none other than T.E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia). Lawrence was beyond passionate about motorcycles. Over the years following his famous North African campaign in World War I, Lawrence owned seven Brough Superiors (an eighth was being built when he passed away).

Although Lawrence was famous, he was far from rich, choosing the pricey Broughs purely out of his love for fine craftsmanship and desire to own the fastest production motorcycle of its time. He routinely went on highly spirited rides on the backroads of England, conveying the experience with colorful language. I think his words could stir even the most sedate and passionless person.

The Mint

In his novel The Mint (published posthumously) Lawrence engages some of his most poetically loquacious wanderings to describe an outing on his Brough Superior, which he named Boanerges (ancient Greek translating to “son of thunder”). Lawrence was in the habit of making regular 100-mile jaunts—at speed—from his Royal Air Force base near Nottingham, England, to visit various bakeries, cafes, and butcher shops to collect the makings for his evening meal.

In chapter 16, titled The Road, Lawrence speaks of the Brough’s potential, writing:

“The engine’s final development is fifty-two horse-power. A miracle that all this docile strength waits behind one tiny lever for the pleasure of my hand. Another bend: and I have the honour of one of England’s straightest and fastest roads. The burble of my exhaust unwound like a long cord behind me. Soon my speed snapped it…”

Lawrence goes on to describe racing a Bristol Fighter aircraft from a neighboring aerodrome.

“The pilot pointed down the road towards Lincoln. I sat hard in the saddle, folded back my ears and went after him, like a dog after a hare. … Through the plunges of the next ten seconds I clung on, wedging my gloved hand in the throttle lever so that no bump should close it and spoil our speed.”

Then, after having caught the plane, he writes:

“I dared, on a rise, to slow imperceptibly and glance sideways into the sky. There the Bif was, two hundred yards and more back. Play with the fellow? Why not? I slowed to ninety: signaled with my hand to overtake. They were hoping I was a flash in the pan, giving them best. Open went my throttle again. Boa [short for Boanerges] crept level, fifty feet below: held them: sailed ahead into the clean and lonely country.”

Lawrence summed up the chapter thusly:

“A skittish motor-bike with a touch of blood in it is better than all the riding animals on earth, because of its logical extension of our faculties, and the hint, the provocation, to excess conferred by its honeyed untiring smoothness. Because Boa loves me, he gives me five more miles of speed than a stranger would get from him.”

Amen.